Total-evidence dating

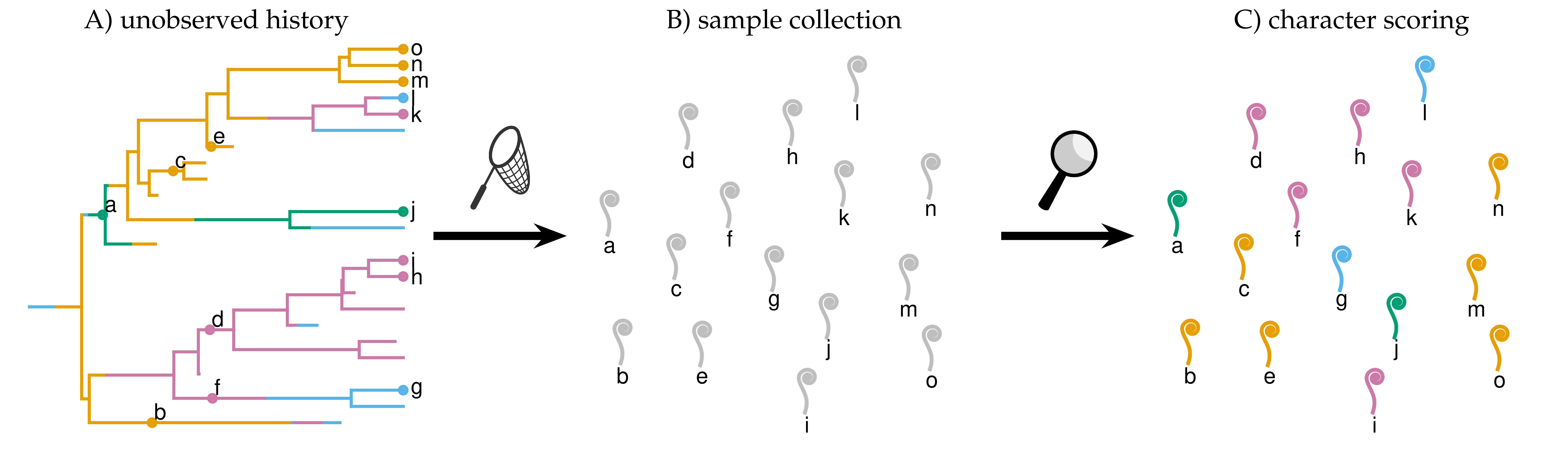

Time-calibrated phylogenies (trees with branches measured in calendar time) are fundamental to understanding how lineages diversify and evolve over time. The standard method for calibrating phylogenies requires the researcher to express their belief about the age of particular clades in the form of calibration densities. Eliciting calibration densities is often very difficult because it relies on the researcher’s understanding of the fossil record (and the processes that generate it) and of the relationship between fossils and extant lineages. Total-evidence dating is an emerging alternative for estimating time-calibrated phylogenies for fossil and living taxa from combined molecular and morphological datasets (Ronquist et al. 2011 Syst. Biol., Zhang et al. 2016 Syst. Biol.).

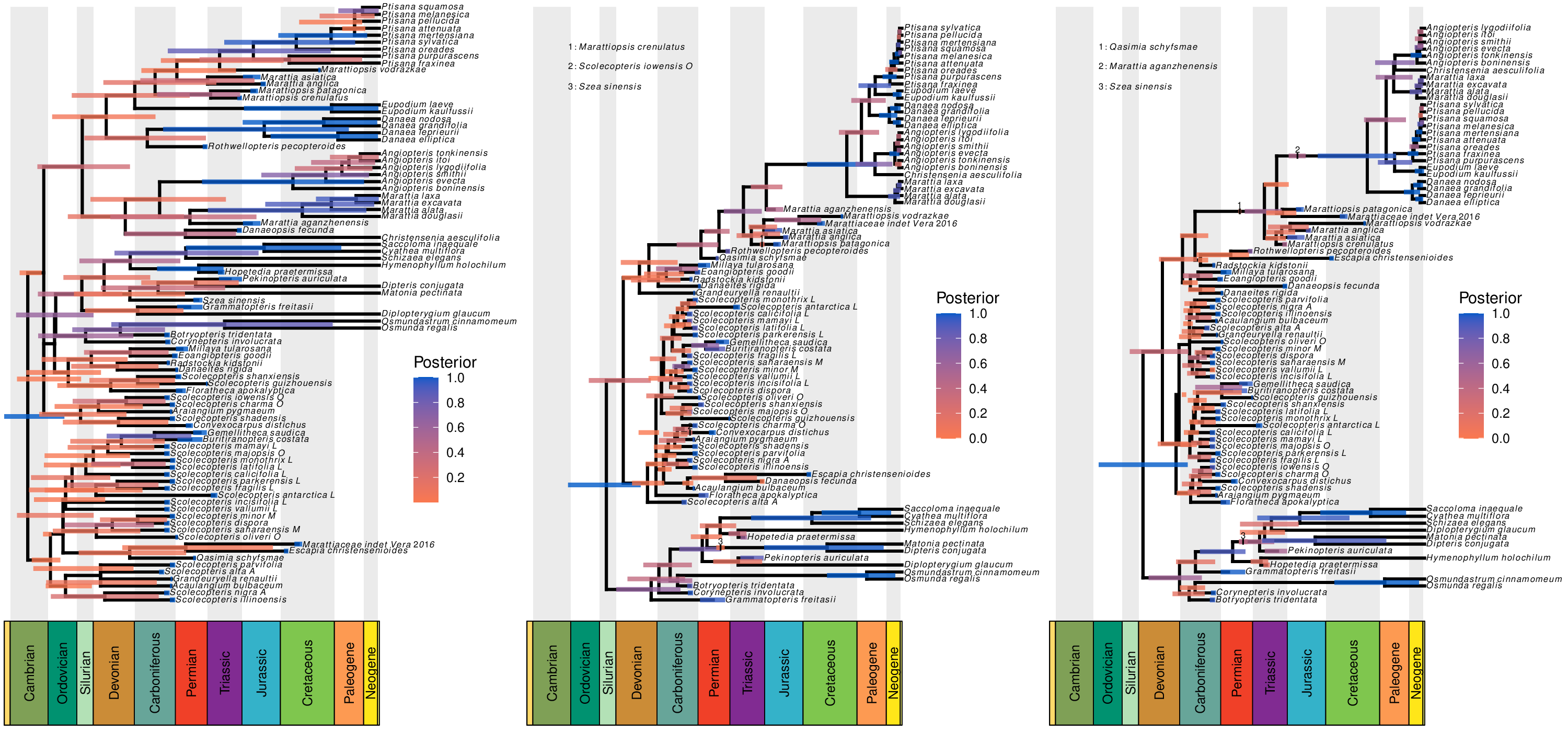

The strength of total-evidence dating comes from replacing potentially arbitrary calibration densities with statistical models that describe how traits evolve and how lineages diversify (and are ultimately sampled to produce the fossil record). One of my research goals is to understand the impact of different modeling choices on total-evidence dating. Together with my colleagues, I explored the impact of model specification on total-evidence-based divergence-time estimates in the marattialean ferns over a large model space, showing that our assumptions about how lineages diversify (speciate and go extinct) have a much larger impact on phylogenetic estimates than do our assumptions about how morphological characters evolve. This work highlights the need for careful evaluation of the lineage diversification model.

Our study of the marattialean ferns demonstrates that the choice of tree prior can have a large impact on divergence-time estimates, so careful model choice is an important aspect of total-evidence dating. However, our study also a counterintuitive result: despite the fact that most of our fossils come from the Pennsylvanian period, allowing fossilization rates to vary over time always reduced model fit. In followup work, I used Bayesian theory and simulation to show that this was due to treating birth-death models as priors; because these models have parameters that produce observations (fossils and extant species), some of their probability should be associated with the likelihood of the model. While it has no impact on parameter estimates for a given model, failing to treat the probability of the samples as part of the likelihood function compromises our ability to compare among tree models. This exploration allows us to predict the magnitude of the error, and to propose remedies (some more practical than others).

Selected publications on total-evidence dating

- May, M. R. & Rothfels, C. J. (2021). Mistreating birth-death models as priors in phylogenetic analysis compromises our ability to compare models. bioRxiv. link.

- May, M. R., Contreras, D. L., Sundue, M. A., Nagalingum, N. S., Looy, C. V., & Rothfels, C. J. (2021). Inferring the Total-Evidence Timescale of Marattialean Fern Evolution in the Face of Model Sensitivity. Systematic Biology, in press. link.

Lineage diversification

Rates of lineage diversification (speciation and extinction) change over time and across the branches of the tree for many reasons. In ongoing work, I’m developing a Bayesian method for inferring how rates of diversification vary among lineages in a trait- and time-agnostic framework. The method allows diversification-rate shifts along extinct branches (and is therefore a statistically principled alternative to BAMM), and allows rate shifts to occur independent of speciation events (in contrast to CLaDS, which assumes rate shifts occur at speciation events).

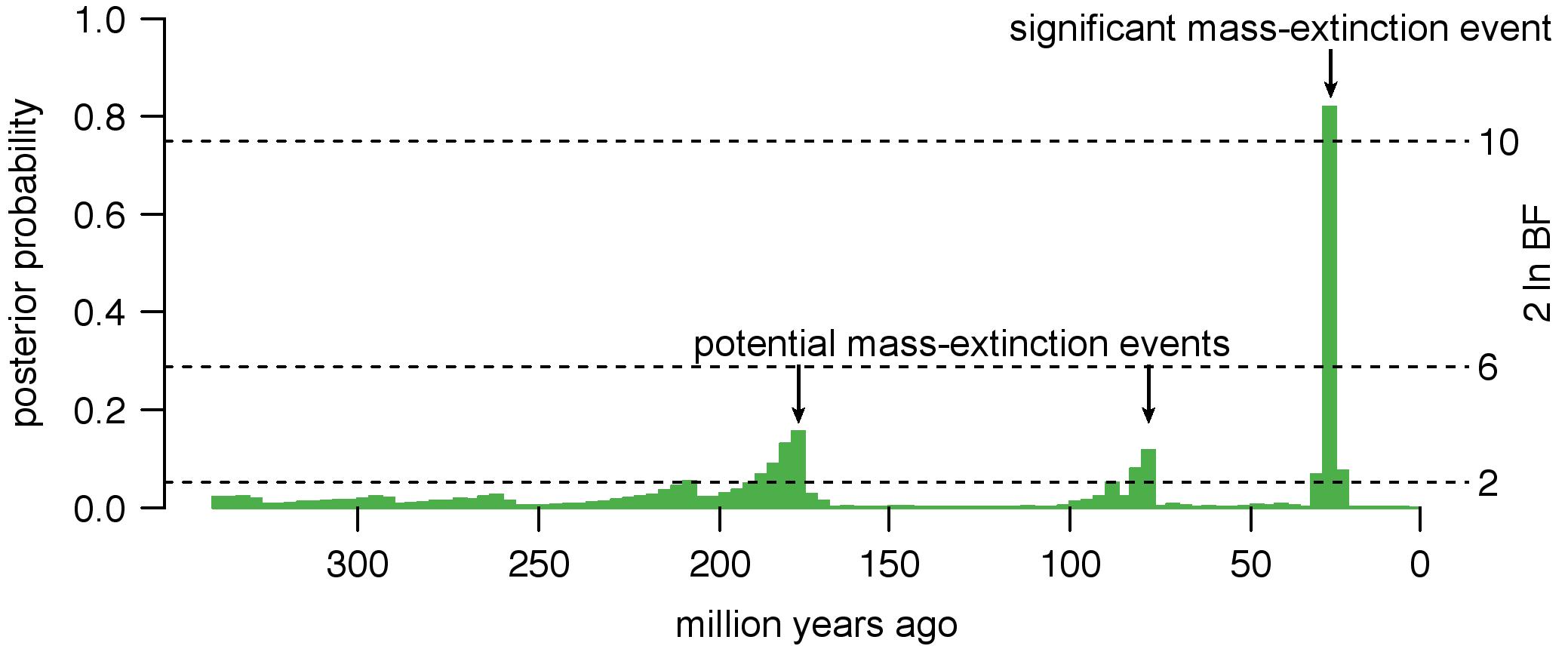

Mass-extinction events have profound consequences on the accumulation of lineages through time. However, the signature of mass-extinction events on molecular phylogenies can be difficult to distinguish from other processes that may be biologically common; for example, increases in net-diversification rates (speciation minus extinction) can result in lineage-accumulation curves that are similar to those caused by mass-extinction events. Failure to accommodate diversification-rate variation may therefore cause us to make errors in inferring the number, timing, and magnitude of mass-extinction events. To tackle this problem, I developed a Bayesian method, CoMET, that allows us to robustly infer the impact of mass-extinction events against a background of variation in rates of speciation and extinction.

Selected publications on lineage diversification

- S., Höhna, Freyman, W. A., Nolen, Z., Huelsenbeck, J. P., May, M. R., & Moore, B. R. (2021). A Bayesian approach for estimating branch-specific speciation and extinction rates. bioRxiv. link.

- May, M. R., Höhna, S., & Moore, B. R. (2016). A Bayesian approach for detecting the impact of mass-extinction events on molecular phylogenies when rates of lineage diversification may vary. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 7(8), 947–959. link.

- May, M. R. & Moore, B. R. (2016). How well can we detect lineage-specific diversification-rate shifts? A simulation study of sequential AIC methods. Systematic Biology 6(65), 1076–1084. link.

- Moore, B. R., Höhna, S., May, M. R., Rannala, B., & Huelsenbeck, J. P. (2016). Critically evaluating the theory and performance of Bayesian analysis of macroevolutionary mixtures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 34(113), 9569–9574. link.

Character evolution

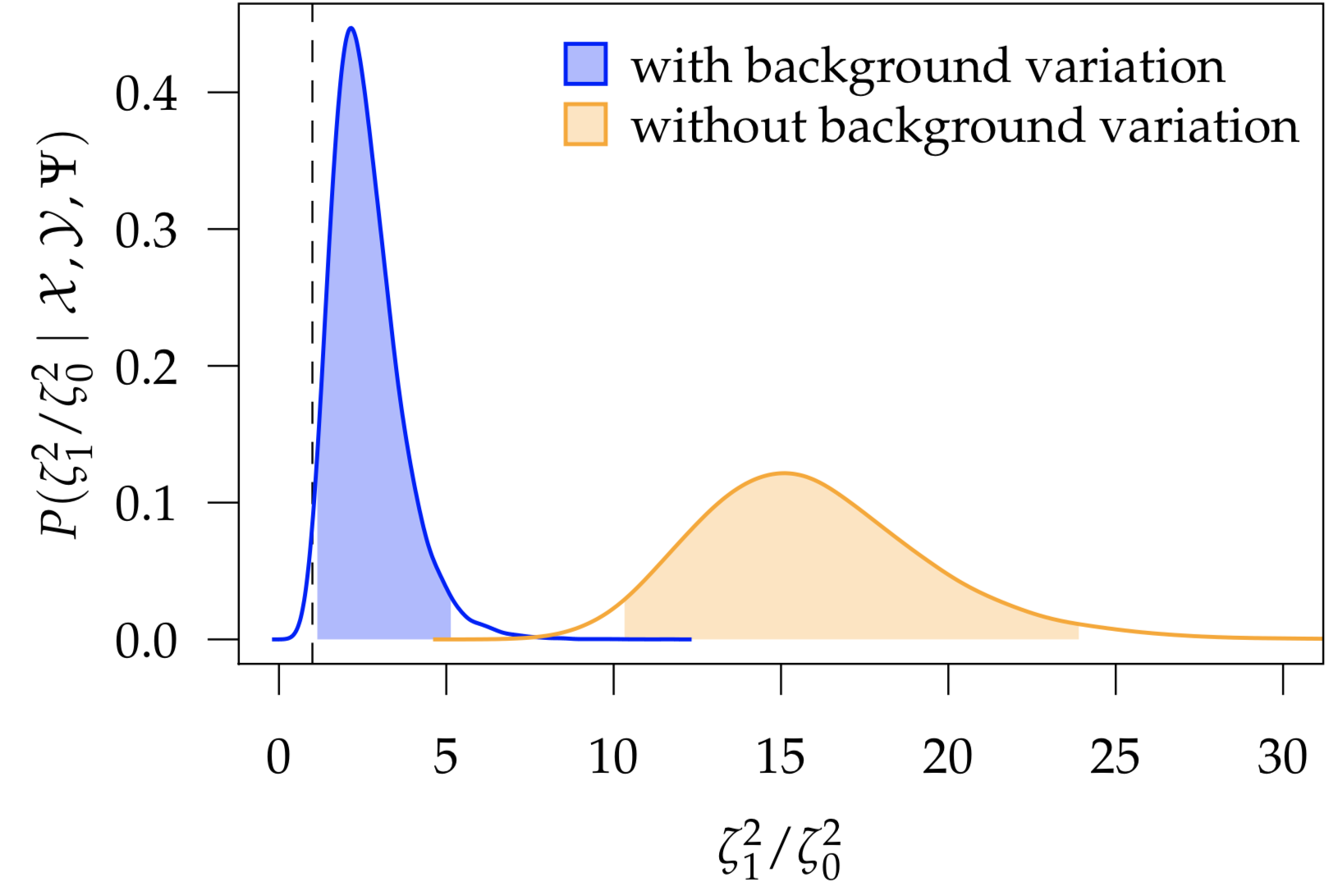

Many macroevolutionary studies seek to understand how rates of trait evolution depend on the state of some other variable; for example, have reef-dwelling fish—owing to increased habitat complexity and ecological opportunity—experienced increased rates of morphological evolution relative to their non-reef-dwelling relatives? However, we expect rates of trait evolution to vary for many reasons; even within clades that are entirely reef-dwelling, we can easily imagine that rates of continuous-trait evolution may vary owing to a variety of other ecological and life-history factors. I developed a Bayesian method for inferring how rates of continuous-trait evolution vary according to a discrete trait of interest, while controlling for background sources of rate variation. I implemented this method, MuSSCRat, in the Bayesian phylogenetic software RevBayes.

Selected publications on character evolution

- May, M. R. & Moore, B. R. (2020). A Bayesian Approach for Inferring the Impact of a Discrete Character on Rates of Continuous-Character Evolution in the Presence of Background-Rate Variation. Systematic Biology 69(3), 530–544. link.

Software development

I’m a developer on the RevBayes, a flexible platform for Bayesian (mostly) phylogenetic analysis. Many of the methods I describe above are implemented in RevBayes. I contribute to and maintain many RevBayes tutorials, especially for models of continuous-character evolution.

I’m also (along with Carrie Tribble) a lead developer on RevGadgets, an R package for visualizing and summarizing RevBayes output. Check it out on GitHub!

Selected publications on Software

- Tribble, C. M., Freyman, W. A., Landis, M. J., Lim, J. Y., Barido-Sottani, J., Kopperud, B. T., Höhna, S. & May, M. R. (2021). RevGadgets: an R Package for visualizing Bayesian phylogenetic analyses from RevBayes. Methods in Ecology and Evolution (), . link.

- Höhna, S., May, M. R., & Moore, B. R. (2016). TESS: an R package for efficiently simulating phylogenetic trees and performing Bayesian inference of lineage diversification rates. Bioinformatics 5(32), 789–791. link.